Newsletter

New posts straight to your inbox.

Join Our Newsletter and Get the Latest

Posts to Your Inbox

Why the Australian Frontier Wars are important

Why the Australian Frontier Wars are important

Australia is built on the Frontier Wars

The 2022 SBS/NITV documentary, The Australian Wars, showed the importance of the Frontier Wars in building modern Australia. Historian Henry Reynolds, author of many books on Australia’s black history, summarised what these wars meant for Indigenous people and for Australia:

[It] was about unbelievably important things for them. It was whether or not they could control the way the land was managed, and it was ultimately about their very survival and the very survival of their cultures and traditions. It was war because of what it was about, not the way it was fought. And my view is, not only was it war but it was our most important war. One, it was fought in Australia, two, it was fought about Australia and, three, it determined the ownership and the control, the sovereignty of a whole continent. Now, what can be more important than that—to us? (The Australian Wars, episode 3, 2022)

Rachel Perkins, Arrernte and Kalkadoon woman and Director of The Australian Wars, spoke in similar but more personal terms, as she stood on land that had seen a massacre of her ancestors:

My evidence for war is that my people’s land is owned by others in vast cattle stations … Until it is recognised as a war and memorialised as a war, it will never be entirely over … And this is the glorious history of Australia. It’s not all of the story of Australia but it’s a foundational part of it and it sits alongside the story of the First Fleet, which was another glorious moment in Australia that directly led to this.

And it’s also a story about war and the people who lost their lives in war, the same number of people who lost their lives in all of the wars Australia’s ever been involved in. And surely this story deserves to be remembered. Lest We Forget. (The Australian Wars, episode 3, 2022)

‘These were the wars that were fought in Australia’, said Perkins, ‘and they were the wars that really made the modern Australian state’. And that is the key point.

The Frontier Wars are truly, as the title of Perkins' documentary says, 'The Australian Wars'. They were fought not just on the Frontier but, as Henry Reynolds says, for ownership and control of the whole land, for sovereignty. (Some people have called them 'the Homeland Wars'.) We will use the term 'the Australian Wars' from now on in this article.

None of the wars traditionally commemorated in the Australian War Memorial and other such shrines have that characteristic of fighting for sovereignty. Those wars are more accurately labelled 'Australia's overseas wars'.

The Australian Wars killed tens of thousands of Australians

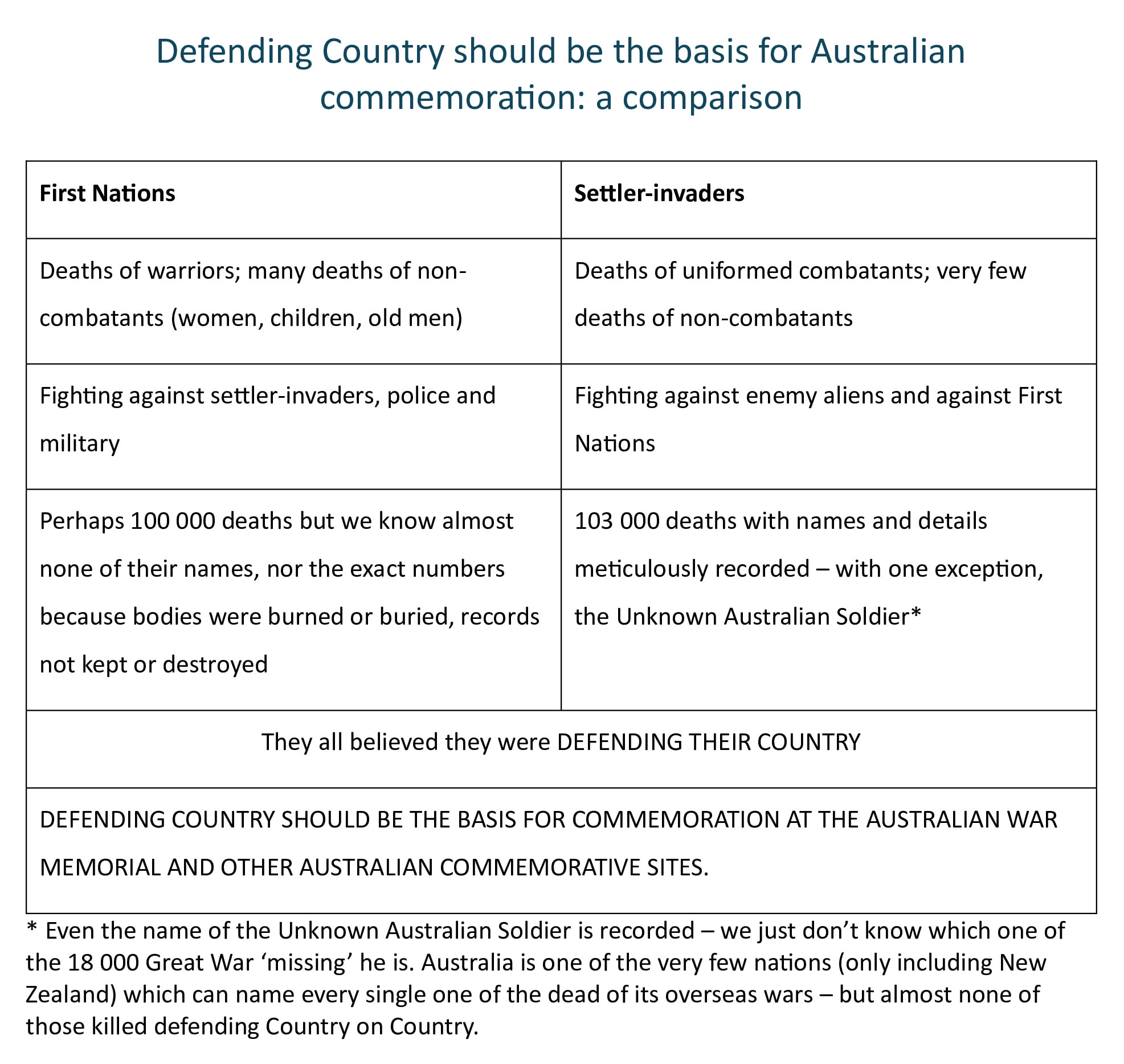

The Australian Wars killed somewhere between 20 000 and 100 000 Indigenous Australians, men, women, and children, as well as perhaps 2500 settler-invaders, police (including native police), and soldiers.

If the number killed was indeed as high as 100 000, that is around the same number as died in all the wars now commemorated on the Roll of Honour at the Australian War Memorial. We have firmed up that Roll of Honour number down to the last dead Anzac, yet we have had to punt for a rough approximation of the Indigenous figure.

Much of that uncertainty is because we just do not know the Australian (Frontier) Wars numbers, because exact numbers were not recorded, because deaths were hushed up, because bodies were burned or buried. There is little point, however, arguing about what is the precise number of deaths in the Australian Wars. The bigger point is the uncertainty about precise numbers and the things that were done or not done to obscure those numbers.

The possibility of reducing that uncertainty is partly also because Australians largely have been raised on war stories of ‘our boys’ fighting gamely in trenches and jungles, coming through against great odds or taking part in massed invasions or bombing raids. Many Australians do not recognise the Australian (Frontier) Wars as ‘real war’, and so do not care about counting those dead.

Intergenerational trauma cannot be left in the silence

The work of historians like Marina Larsson and Laura James, Bruce Scates and Rebecca Wheatley has reminded us that, in our overseas wars, as well as those 100 000 or so deaths, there were many times that number left mentally and physically damaged, to be cared for by their families and society. That legacy could be given the term ‘intergenerational trauma’.

That term applies just as much to today’s First Australians, whose ancestors were scarred by the massacres and resistance of the Australian Wars. For Indigenous Australians, however, stories of these wars passed down through families have accompanied stories of stolen generations, stolen wages, forced adoptions, as well as the disproportionate incarceration of Indigenous people and the other ‘Gaps’ today’s bureaucrats plot assiduously.

So, intergenerational trauma is another reason why the Australian Wars are important. There is just as much reason to make reparations for the Australian Wars at our national - Australian - war memorial and in our national commemorations as there has been for apologising for stolen generations and forced adoptions. In all of these cases, the effects are felt long after the original actions.

Some non-Indigenous Australians, like John Howard when prime minister, claim that Australians today cannot be held responsible for what happened to Indigenous Australians decades ago. That is not the point. The point is that Australians today, Indigenous and non-Indigenous, confront the trauma that has flowed from those past events and, together, Australians today need to deal with that trauma as it exists today.

Guilt for those past events may not be inherited; responsibility for dealing with their effects is. We can, on Anzac Day and other days, feel pride for what our forebears have done in wars. Why then can we not feel embarrassment or shame for the other deeds of our forebears?

We do not hide behind 'We weren't there, we didn't do it, we're not responsible!' when we commemorate our overseas wars. Why then do we apply that dodgy argument to the Australian Wars?

'People now seem to believe’, wrote Michael McGirr in 2004, ‘that in looking at the Anzacs they are looking at themselves. They aren’t. The dead deserve more respect than to be used to make ourselves feel larger’ (page 246). We take credit for - even bask in - what we see as the good parts of our war history, while turning away from the bad, and we probably do both even more now than when McGirr wrote.

Surely it is not legitimate to have only positive feelings about our past. It is often said that we enjoy freedom purchased with the lives of those who defended us and that we owe those men and women respect for the (willing) sacrifice they made. As we enjoy the prosperity built on the dispossession of First Nations peoples, do we not also owe them respect for the (unwilling) sacrifice they made?

For generations, many Australians have tried to ignore the Australian Wars, just as we have tried not to look at those other causes of trauma today. In his famous Boyer Lectures of 1968, anthropologist WEH Stanner spoke of ‘the great Australian silence’.

It is a structural matter, a view from a window which has been carefully placed to exclude a whole quadrant of the landscape. What may well have begun as a simple forgetting of other possible views turned under habit and over time into something like a cult of forgetfulness practised on a national scale.

Perhaps that is not as true as it was in 1968. Perhaps. What happens at the Australian War Memorial on the Australian Wars will be one indicator of how much we have changed.

On occupying new territory the aboriginal inhabitants are treated in exactly the same way as the wild beasts or birds the settlers may find there. (Journalist Carl Feilberg, Queenslander, May 1880, quoted in David Marr, Killing for Country, pp. 398-99)

What we commemorate shows what we regard as important

The Australian Wars are important because, when we properly acknowledge and commemorate them, we build on symbolism—Welcomes to and Acknowledgement of Country, renaming of places and geographical features (Naarm, Uluru, Wiradjuri Country), AFL Dreamtime Round—with a crucial change at one of our most important cultural institutions (some would say, ‘our most sacred place’), the Australian War Memorial.

Beyond that, there are the potential implications of that act of acknowledgement and commemoration for our other commemorative places and practices, from local memorials and ceremonies to Anzac Day and Remembrance Day.

What a nation commemorates shows what it regards as important. A nation which embraces the concept of Defending Country, a nation which does not distinguish by skin colour or descent or the identity of the enemy the worth of ‘service and sacrifice’ to defend Country, is a different nation from what went before. That is the kind of Australia which could grow from real change at the War Memorial.

Some of us use the term ‘service and sacrifice’ to apply to what has traditionally been the focus of the Australian War Memorial. What is the difference between the sacrifice made by a First Australians warrior—and often his family and children—defending their Country, and that made by a uniformed soldier, sailor or flyer defending Australia?

Australians have placed a high value on ‘service and sacrifice’ by Australians in wars fought overseas. Extending this to service and sacrifice by Australians in wars fought on Country should be an easy and obvious step.

The burden of proving that there is a difference between these two forms of service and sacrifice lies on the opponents of the proper recognition and commemoration of the Australian Wars at the Memorial. The fact that Indigenous families—as well as warriors—were killed or wounded in the Australian Wars makes those wars more like wars in the rest of the world—World War I, World War II, Vietnam, Ukraine, Yemen, Gaza—not less.

Millions of civilians died in those overseas wars. The wars that have been until now the main concern of the War Memorial have directly killed or wounded very few Australians not in uniform. An American study estimated that during the 20th century around 231 million people died in wars and conflict. This figure covered, of course, huge numbers of civilian as well as military deaths.

By contrast, Australian deaths in war during the twentieth century amounted to around 100 000, or about 0.04 per cent of the total world-wide deaths—and they were almost entirely military, men and women wearing the King’s or Queen’s uniform. The lack of civilian deaths in what Australians have traditionally regarded as wars should not prevent us reframing our attitudes, to treat as wars the Australian Wars, where the deaths of women, children and other non-combatants were very much part of the story.

We need to close the Commemoration Gap

Having the Australian War Memorial properly ‘own’ the Australian Wars would go a long way towards closing the Commemoration Gap, which is as wide as any other gap affecting First Australians. Again, what we commemorate as a nation shows what we regard as important. What we commemorate becomes important. Failing to properly commemorate the Australian Wars shows we do not regard them as important.

In the words of the then Minister for Indigenous Australians, Linda Burney, ‘a failure to see [the Australian Wars] reflected in this key institution [the Memorial] would be jarringly out of step with this new phase of national reckoning’. Australian Wars Truth-telling at the Memorial is an idea whose time has come.

The Australian War Memorial must include an honest, evidence-based, non-sanitised presentation and commemoration of the Australian Wars, and that presentation and commemoration must occupy floor space at the Memorial commensurate with the importance of those wars in our history.

![Governor Lachlan Macquarie: Instructions to Captain W G B Schaw, Captain James Wallis and Lieutenant Charles Dawe, commanding detachments of 46th Regiment proceeding on punitive expedition against hostile natives in the Nepean, Hawkesbury and Grose valleys, 9 April 1816: MHNSW-StAC: NRS 897 [4/1735] pp 1-13](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/6458782c604430811f691cd9/6507c4449323df393e9d05c6_LAB4.5_Macquarie_intructions-1000px.jpg)

Governor Lachlan Macquarie effectively declared war on the Aboriginal peoples of New South Wales. He authorised a campaign of “terror” against those “hostile natives” who didn’t submit to colonial rule: permitting them to be killed, and their bodies hung up in the trees as grisly warnings, or taken hostages as “prisoners of war”. Military campaigns sought to punish Aboriginal people for their resistance, but as British subjects they were also meant to be protected under British law. The Appin Massacre of Aboriginal men, women and children on 17th April 1816 was the result of Macquarie’s orders for members of the 46th Regiment to lead punitive expeditions in the Liverpool district, Hawkesbury, Nepean and Grose Valleys.

'I have directed as many Natives as possible to be made prisoners, with the view of keeping them as Hostages until the real guilty ones have surrendered themselves or have been given up by their Tribes to summary Justice. – In the event of the Natives making the smallest show of resistance – or refusing to surrender when called upon so to do – the officers Commanding the Military Parties have been authorized to fire on them to compel them to surrender; hanging up on Trees the Bodies of such Natives as may be killed on such occasions, in order to strike the greater terror into the Survivors.'

Governor Lachlan Macquarie, Governor’s Diary & Memorandum Book Commencing on and from Wednesday the 10th Day of April 1816.

Updated 6 March 2024, 3 February 2025, 27 February 2025.

You may also be interested in the related articles …